what are environmental factors that contribute to malaria

- Enquiry

- Open Access

- Published:

Ecology and meteorological factors linked to malaria transmission effectually large dams at three ecological settings in Ethiopia

Malaria Journal book xviii, Commodity number:54 (2019) Cite this commodity

Abstruse

Groundwork

A growing torso of testify suggests that dams intensify malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. However, the environmental characteristics underpinning patterns in malaria transmission around dams are poorly understood. This study investigated local-scale environmental and meteorological variables linked to malaria transmission around iii large dams in Ethiopia.

Methods

Monthly malaria incidence information (2010–2014) were nerveless from health centres around three dams located at lowland, midland and highland elevations in Ethiopia. Environmental (elevation, distance from the reservoir shoreline, Normalized Deviation Vegetation Index (NDVI), monthly reservoir water level, monthly changes in h2o level) and meteorological (atmospheric precipitation, and minimum and maximum air temperature) data were analysed to determine their relationship with monthly malaria manual at each dam using correlation and stepwise multiple regression analysis.

Results

Village altitude to reservoir shoreline (lagged past one and 2 months) and monthly change in water level (lagged by one calendar month) were significantly correlated with malaria incidence at all iii dams, while NDVI (lagged by 1 and 2 months) and monthly reservoir water level (lagged by 2 months) were found to have a significant influence at only the lowland and midland dams. Precipitation (lagged by one and two months) was also significantly associated with malaria incidence, but only at the lowland dam, while minimum and maximum air temperatures (lagged by one and 2 months) were important factors at only the highland dam.

Conclusion

This study confirmed that reservoir-associated factors (distance from reservoir shoreline, monthly boilerplate reservoir h2o level, monthly water level change) were important predictors of increased malaria incidence in villages around Ethiopian dams in all peak settings. Reservoir water level management should be considered as an additional malaria vector control tool to help manage malaria transmission effectually dams.

Groundwork

Malaria is a serious public wellness challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, with an estimated 200 million cases of malaria in 2017 alone [1]. This region accounts for 92% of the global malaria brunt [1]. A number of environmental, climatic, seasonal, and ecological factors determine the occurrence and intensity of malaria manual. For case, while rainfall limits the availability of breeding habitats for mosquito vectors, temperature determines the length of musquito larvae development and the rate of growth of the malaria parasites inside the vector [2, 3]. In addition, environmental modifications, such every bit the construction of dams and irrigation schemes, likewise touch on the type and distribution of mosquito convenance habitats [4, 5].

In Africa, dams have been demonstrated to raise rates of malaria manual in areas of unstable manual [5, 6]. Increased malaria incidence post-obit dam construction was reported around several African dams [7,viii,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Overall, dams have been shown to contribute to over 1 million malaria cases annually in sub-Saharan Africa [15]. Even so, the extent to which diverse environmental and climatic factors may have contributed to enhanced rates of malaria transmission effectually these sites remains poorly understood.

Climatic variables such as precipitation and air temperature are of import determinants of the spatial distribution and relative abundance of malaria vector species in Africa [16]. For instance, in Africa, Anopheles gambiae is the predominant species in high rainfall environments, while Anopheles arabiensis is more common in barren areas [17, 18]. Withal, climatic conditions are besides inter-related with elevation. For example, air temperature decreases as meridian increases, and consequently the affluence and species composition of malaria vectors may change significantly with elevation [sixteen].

In Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, local increases in malaria rates have been blamed on the institution of new dams [9, 10, 12,13,14]. A new era of dam construction currently underway in Ethiopia [19] has also elevated concerns for the public health affect of these infrastructures. Notwithstanding, dams are of import contributors to Federal democratic republic of ethiopia's economic evolution and nutrient security. Notwithstanding, a poor agreement of their effects on malaria transmission in different ecological settings represents a disquisitional barrier to the sustainability of water storage infrastructures.

Understanding how different environmental and climatic factors affect rates of malaria transmission is required to develop appropriate disease control tools. A recent review suggested that the relationship between dams and malaria incidence varies beyond ecological settings [15]. However, the report did not investigate how ecology (other than the presence of dams) and climatic factors vary beyond these ecological settings and, in turn, bear upon rates of malaria incidence around dams. The present study aims to investigate relationships among a number of environmental and meteorological factors associated with malaria manual around Ethiopian dams in three ecological settings: highland, midland and lowland elevations.

Methods

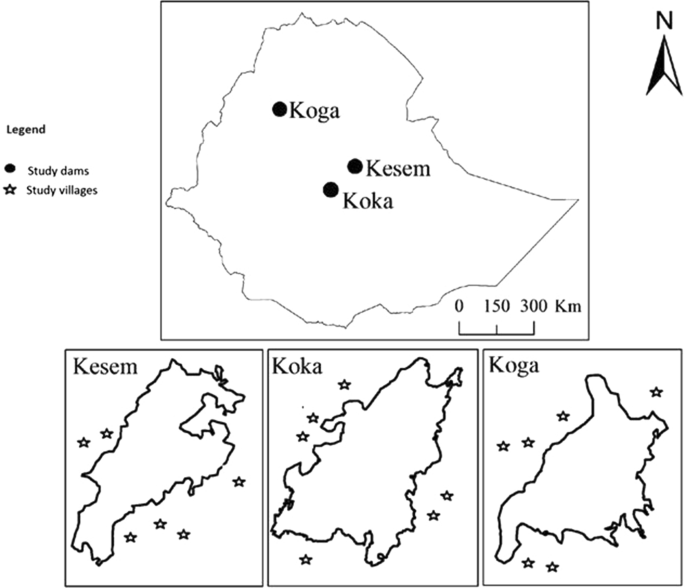

The present study was conducted around three dams in Ethiopia: Kesem Dam [975 chiliad above sea level (asl)], Koka Dam (1551 m asl) and Koga Dam (1980 1000 asl) (Fig. 1). At each dam, half-dozen villages within a v-km radius of the reservoir shoreline were randomly selected for this written report. Simply villages located upstream of the dam were included to avoid potentially confounding influences of the downstream river surround. Fourth dimension series malaria case data as well equally environmental and meteorological information were analysed to make up one's mind factors linked to malaria manual at each dam setting.

Map of the report area and location of study villages in relation to the reservoir shorelines

Kesem Dam (hereafter referred equally the lowland dam) is located on the Brimful River in the lowlands of the Ethiopian Rift Valley, 225 km east of Addis Ababa, the capital of Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. Its crest height of 25 one thousand stores a maximum of 500 million cu m of h2o, covering an area of 200 sq km. The maximum length of the shoreline at full capacity is 55.4 km. The primary purpose of the dam is to irrigate 20,000 ha of state for sugarcane production downstream. The area is characterized equally semi-arid with a mean daily temperature of 27 °C. The hottest month is May (hateful daily temperature is 38 °C) and the coldest is December (average daily temperature is eighteen °C). The surface area receives an average annual total rainfall of 600 mm; the main rainy season (June to August) accounts for 80% of the total rainfall. An estimated population of 35,000 lives inside a 5-km radius of Kesem reservoir [20].

Koka Dam (future referred every bit the midland dam) is located in the Ethiopian Rift Valley in Central Ethiopia, 100 km s of Addis Ababa. It has a crest height of 42 m, and a full water storage chapters of 1188 one thousand thousand miii. The surface area of the reservoir at total capacity is 236 sq km and the length of the reservoir at total storage capacity is 86 km. The primary purpose of the dam is to generate 43.2 MW of electricity from three turbines (approximately 6% of the current full filigree-based generating capacity of the state). Currently, the Wonji sugarcane irrigation scheme (6000 ha), located approximately 12 km downstream of the dam, is besides dependent on releases from Koka Dam. In add-on, the dam is used for flood control. The surface area receives a full annual rainfall of 850 mm and the hateful daily temperature is 22 °C (National Meteorological Agency, unpublished report). The hottest month is May (hateful daily temperature is 29 °C) and the coldest is December (average daily temperature is 12 °C). An estimated population of 29,000 lives within 5 km of the reservoir [xx].

Koga Dam (hereafter referred every bit the highland dam) is located on the Koga River, one of the major tributaries of the Blue Nile River, 560 km northwest of Addis Ababa. The dam has a storage chapters of 83.ane million giii and expanse of 175 sq km. Information technology was deputed in 2009 to irrigate 7000 ha of wheat, corn and teff crops. The rainy season (June to August) generates well-nigh 70% of the run-off feeding the Koga River [21]. The length of the reservoir shoreline at full capacity is 120 km. The area is characterized every bit highland with a mean daily temperature of 19 °C and receives an average almanac rainfall of 1500 mm. The hottest calendar month is May (average daily temperature is 26 °C) and the coldest is January (average daily temperature is 10 °C). An estimated 32,680 people live within 5 km of the reservoir [20].

Malaria is the leading public health challenge in all study villages, peaking betwixt September and November following the months of the rainy flavour (June to August). The inhabitants of the study villages are agrarians, and cattle herding is also mutual. Plasmodium falciparum is the predominant malaria-causing parasite, accounting for lxx–80% of malaria infections (Oromia Health Bureau, unpublished report). The remaining malaria infections are due to Plasmodium vivax. Anopheles arabiensis is the major malaria vector species in the study surface area while Anopheles pharoensis plays a secondary function [12]. Potential mosquito breeding habitats in the study area include shoreline puddles, irrigation canals, rain pools, and human-made pools [22].

Retrospective malaria example data

Five years (January 2010 to Dec 2014) of weekly malaria information were obtained from the health facilities at each of the dam sites. Inhabitants of the written report expanse visit these health facilities to receive medical attention. At each health centre, each febrile case was tested by a trained laboratory technician for malaria using microscopic blood screening to distinguish between P. falciparum and P. vivax. Test results were recorded in the laboratory registry, along with data of outpatient name, age, gender, and residency. These data were de-identified and exported to Microsoft Excel and SPSS for assay. These data were checked for completeness and definiteness by cross-referencing the laboratory registry with the outpatient registry at each clinic. The completeness of the registry ranges from 75 to 82% across the health facilities. A recent external quality assessment of the skills of the microscopists in these health facilities identified that lxxx% of slides were correctly recorded with correct parasite quantification [23]. For quality control, five positive and v negative slides were randomly selected from health facilities each month, and taken to the District Laboratory for re-checking.

Environmental information

The environmental data used for this written report comprised hamlet top, village distance from reservoir shoreline, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and reservoir water level. Village elevation was recorded using a handheld Geographical Positioning System receiver (GPSMAP 60CSx, Garmin International Inc., USA). For each report hamlet, data on monthly altitude from reservoir shoreline were acquired from the European Infinite Agency image repository [24]. These images had a resolution of 150 × 150 m, were geo-referenced, and taken in the beginning calendar week of each month between January 2010 and December 2014. These were and so imported to ArcGIS nine.2 to guess the distance between the middle of each report village and the nearest reservoir shoreline for each calendar month of the report period.

Monthly NDVI data for the written report villages were acquired from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that documents data of the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on-board the Terra and Aqua Satellites. These satellites provide a vegetation survey at a 250-m spatial resolution every 16 days [25]. The MODIS NDVI products are computed from atmospherically corrected, bi-directional surface reflectances that have been masked for water, clouds, heavy aerosols, and deject shadows. NDVI is a measure out of vegetation condition, used here as a proxy for mosquito habitat availability [26]. NDVI values vary between + 1.00 and − 1.00; the higher the NDVI value, the denser the greenish vegetation.

Daily reservoir h2o level data were obtained for each dam from the Ethiopian Electricity and Power Corporation, and the Ministry of Water Resources for the duration of the study menstruum (Jan 2010 to December 2014). These were then exported to Microsoft Excel and SPSS for analysis. The information were aggregated to monthly averages and monthly changes in water level (i.eastward., calculated past subtracting the amount of the reservoir water level (m) at the cease of a month from that at the kickoff of the month; negative values indicate receding water level while positive values bespeak increasing water levels) for each of the three dams. The objective of including monthly changes in water level was to determine how the magnitude of modify in water level correlates with malaria incidence as it directly affects the nature of the shoreline for mosquito breeding habitats.

Meteorological data

Five years (January 2010 to December 2014) of daily meteorological data, including full rainfall (mm), and mean daily minimum and maximum air temperature (°C), were obtained from three meteorological stations at each of the three study dam sites. Any missing values were replaced with daily average information from the closest neighbouring station. Data were and so aggregated to monthly averages and exported to Microsoft Excel and SPSS for analysis.

Statistical analysis

To satisfy the assumptions of individual statistical analyses, first the normality in the distribution of monthly malaria incidence, environmental and meteorological data sets was tested using SPSS. Temperatures (both minimum and maximum), reservoir water level (and change in water level) and NDVI values were usually distributed and analysed every bit explanatory variables. Malaria incidence (dependent variable) and atmospheric precipitation information were found to have a skewed distribution and thus were log-transformed accordingly.

For each hamlet, malaria incidence was calculated as the number of cases per yard population. One-style Assay of Variance (ANOVA), followed by a Tukey's examination, was used to test for the differences in malaria incidence between the three dam sites.

Average monthly meteorological data (precipitation, minimum and maximum air temperature) were calculated and lagged past one and 2 months to allow time for mosquitoes and malaria parasites to consummate their life cycle prior to the expression of whatever malaria incidence. Similarly, monthly NDVI information were as well lagged past one and ii months to allow time for musquito development. Monthly relative humidity information were not included in the analysis due to at that place being too many missing values for the duration of the study menses. To determine whatsoever correlation between meteorological/environmental variables and malaria incidence at each dam site, univariate associations were first examined past regressing unmarried explanatory factors (i.e., ecology and meteorological variables) against malaria incidences for each dam site. Since there might be cross-correlation between independent variables over time, cross-correlation analyses were conducted. When the correlation coefficient for the association betwixt the independent variables was greater than 0.v, these variables were analysed in Autoregressive Integrated Moving Averages (ARIMA) to avoid multicollinearity [27]. After the effect of any auto-correlation had been removed past the ARIMA procedure, stepwise forward multiple regression analyses were used to place the meteorological/environmental factors that best explained malaria incidence at each dam site. Simply those variables with a significant correlation (P < 0.05) with malaria incidence were added in the multiple regression models. Among lagged variables, simply those with the highest correlation (rii > 0.5) were included to these analyses. All analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel and SPSS Version 21 software.

Results

Spatial and temporal variation in malaria incidence

Hateful monthly malaria incidence was 1.7- and v.6-times higher at the lowland dam (mean = 96.three; 95% CI = 81.v–111.0; ANOVA: F = 54.7; P < 0.001) than the midland (mean = 56.7; 95% CI = 45.9–67.iv) and highland dam (mean = 17.2; 95% CI = 13.9–20.four) dams, respectively (Table 1). The temporal variation in malaria incidence at the three dams showed a seasonal superlative between September and November at all study dams (Fig. 2). Differences in malaria incidence between villages and years at each dam site, however, were non statistically significant (ANOVA, P> 0.05). Malaria incidence was mostly strongly correlated with height (r2 = 0.97; P < 0.05): malaria incidence decreased equally summit increased (Fig. 3).

Temporal variation in monthly malaria incidence in reservoir communities at the lowland, midland and highland dams in Ethiopia, 2010–2014

Relationship between malaria incidence and village acme at the lowland, midland and highland dams in Ethiopia

Impact of environmental factors on malaria incidence

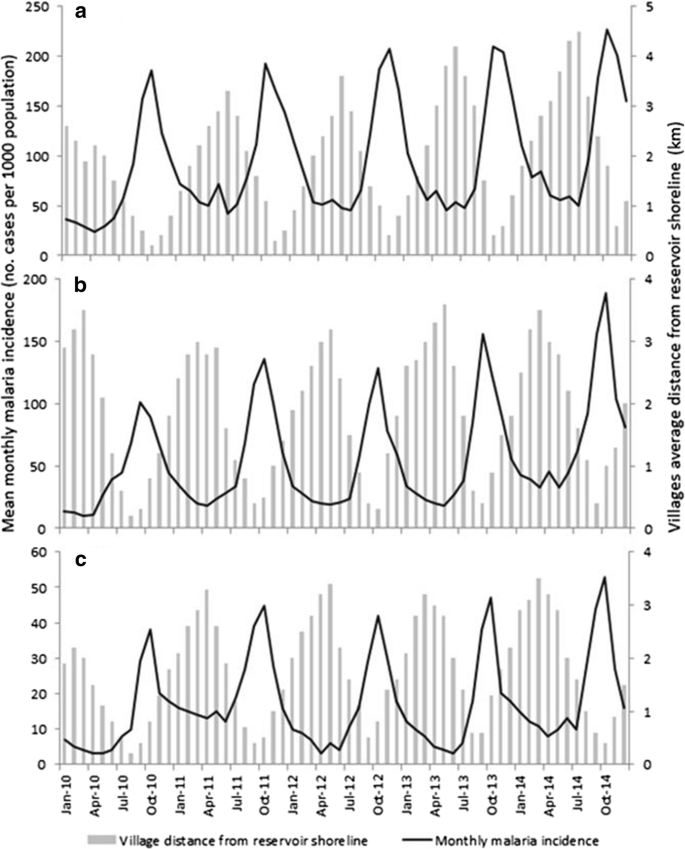

Village proximity to a reservoir shoreline was negatively correlated with malaria incidence in all the three dam sites: the shorter a village'south distance to the shoreline, the higher the malaria incidence in the following calendar month (Fig. iv). Indeed, approximately 69% (annual average from 51 to 86%) of annual malaria cases occurred when a hamlet's altitude was less than 2 km from the shoreline. This tendency was consistent beyond the three dam sites.

Temporal variation in monthly malaria incidence and villages distance from reservoir shoreline at a lowland, b midland and c highland dams in Ethiopia. NB: Y-axis scales vary between the iii plots

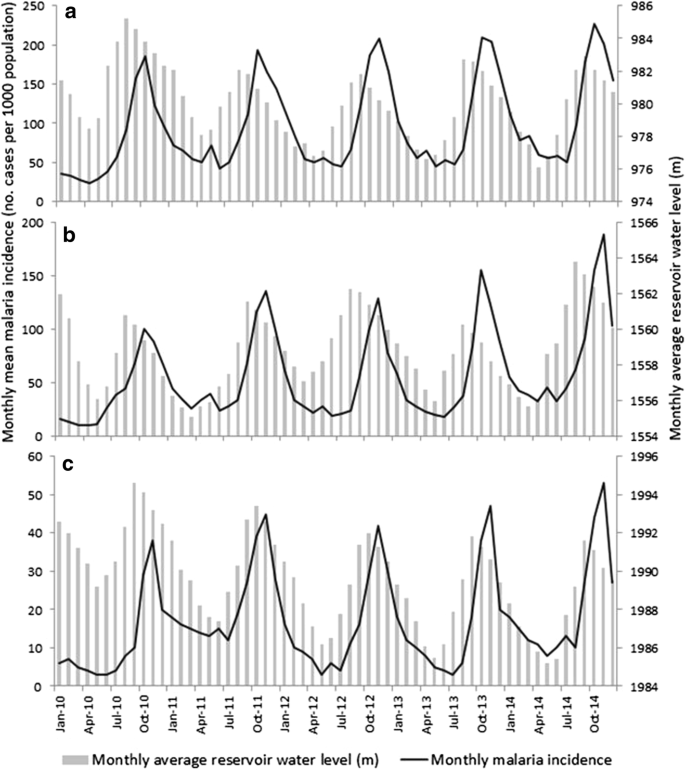

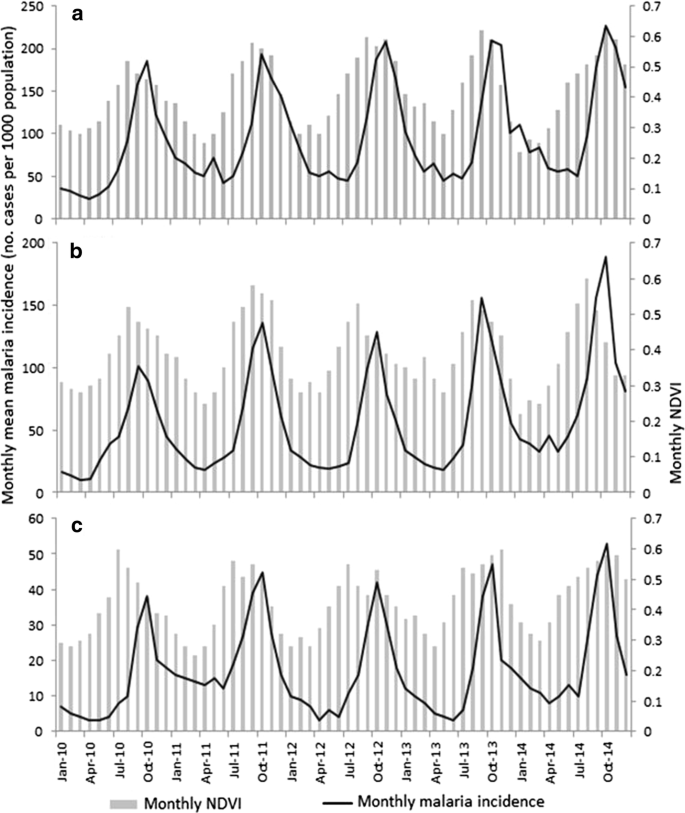

Malaria incidence peaked post-obit the months of high reservoir water level (Fig. five). There was generally a ii-month lag-time between acme h2o level and summit malaria incidence, which was consistent across the dams. Similarly, malaria peaks too followed peaks in positive water level change at each dam (Fig. 6), with a lag-fourth dimension ranging from 1 month (highland dam) to 2–iii months (midland and lowland dams). Likewise, high NDVI levels were associated with peaks in malaria incidence either ane–two (lowland and midland dams) or three months (highland dam) later (Fig. vii).

Temporal variation in monthly malaria incidence and monthly average reservoir water level at a the lowland, b midland and c highland written report dams in Ethiopia, 2010–2014. NB: Y-axis scales vary betwixt the three plots

Temporal variation in monthly malaria incidence and monthly change in reservoir water level at the a lowland, b midland and c highland written report dams, Ethiopia. NB: Y-axis scales vary betwixt the iii plots. Negative water level changes refer to receding h2o levels

Relationship between monthly malaria incidence and monthly NDVI at a lowland, b midland and c highland dams in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. NB: Y-axis scales vary between the iii plots

Univariate analysis detected significant relationships between environmental variables and malaria incidence across the three dams (Table 2). NDVI (lagged by ane and two months; r = 0.567 and 0.669, respectively), hamlet altitude from the reservoir shoreline (lagged past 1 and 2 months; r = − 0.598 and − 0.441, respectively), monthly boilerplate reservoir h2o level (lagged past 2 months; r = 0.362) and monthly modify in reservoir water level (lagged by 1 month; r = − 0.616) were significantly associated with monthly malaria incidence at the lowland dam. At the midland dam, distance from reservoir shoreline (lagged by ane and 2 months; r = − 0.455 and − 0.368, respectively), NDVI (lagged by 2 months; r = 0.452), monthly average reservoir water level (lagged by ii month; r = 0.408) and monthly change in reservoir water level (lagged past ane and two months; r = − 0.481 and − 0.366, respectively) were significantly associated with malaria incidence. At the highland dam, a potent correlation was found between monthly malaria incidence and distance from reservoir shoreline (lagged by 1 and 2 months; r = 0.487 and − 0.377, respectively) and monthly changes in reservoir water level (lagged by 1 month; r = − 0.301).

Bear on of meteorological variables on malaria incidence

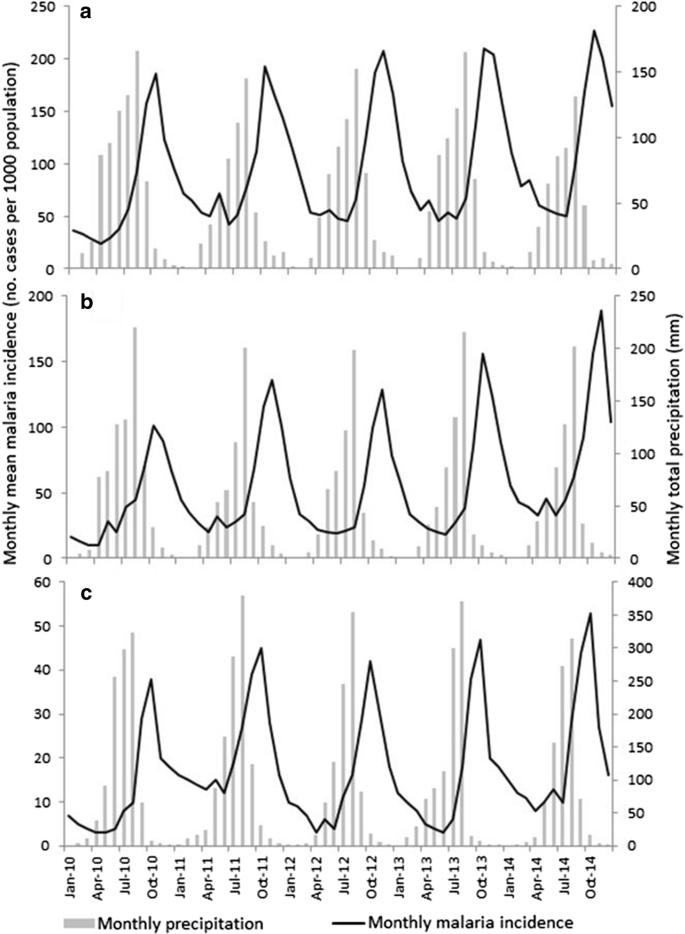

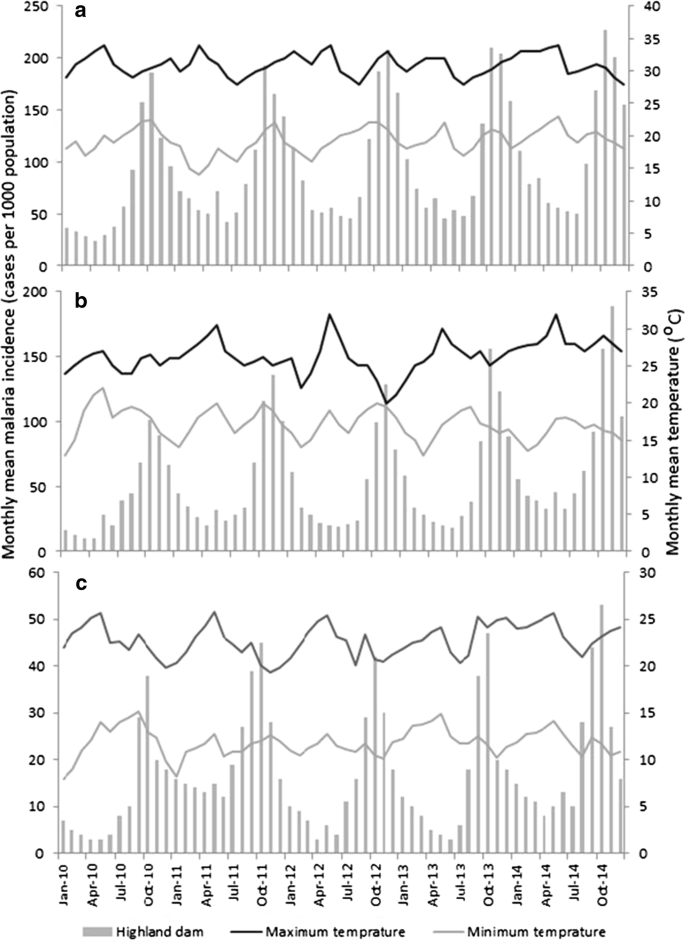

A tiptop in malaria incidence followed mid-year peaks in rainfall at each of the three dams (Fig. 8). Lag times were relatively consistent between dams, ranging from an average of ii.4 or 2.6 months at the lowland and midland dams to ii.0 months at the highland dam. A superlative in malaria incidence tended to occur a calendar month following peaks in minimum air temperature at the lowland and highland dams, but from 1 to ii months following the aforementioned peaks at the midland dam (Fig. 9). However, the relationship between seasonal malaria incidence and variation in maximum air temperature was less articulate. At the lowland dam, malaria peaks occurred 2 to 4 months following tardily-summer troughs in maximum air temperature, but from 0 to 3 months following similar troughs at the midland dam. The same pattern was less consequent at the highland dam, with malaria incidence peaks tending to follow minor September peaks in maximum air temperature.

Temporal variation in monthly malaria incidence and monthly total precipitation at the a lowland, b midland and c highland study dams, Ethiopia. NB: Y-axis scales vary between the three plots

Temporal variation in malaria incidence and minimum and maximum air temperatures at the a lowland, b midland and c highland report dams, Ethiopia. NB: Y-centrality scales vary between the iii plots

Univariate analysis of the influence of meteorological variables on seasonal malaria incidence indicated differences in variables that were significantly associated with malaria incidence between the three dam sites (Tabular array 3). At the lowland dam, monthly total precipitation lagged past 1 and two months (r = 0.414; r = 0.672, respectively) were the but variables with a meaning correlation with monthly malaria incidence. At the midland dam, monthly full precipitation lagged past 2 months (r = 0.329) and monthly hateful minimum temperature lagged by one and 2 months (r = 0.501; r = 0.612, respectively) were significantly correlated with monthly malaria incidence. At the highland dam, monthly hateful minimum (r = 0.419; r = 0634) and maximum (r = 0.364; r = 0.451) air temperature lagged by i and 2 months were significantly correlated with monthly malaria incidence.

Regression models

Cross-correlation assay showed that a number of environmental and meteorological variables were significantly correlated with each other (see Additional file 1: Table S1). For instance, maximum temperature was significantly correlated with NDVI, monthly reservoir water level and reservoir h2o level change at each of the three dams.

Stepwise multiple regression analyses selected few environmental and meteorological variables as factors near explaining malaria incidence across the three study dams (Table 4). At the depression land dam, village distance to reservoir shoreline lagged past 1 month (rii = 0.468; P < 0.001), monthly boilerplate change in reservoir water level lagged by 2 months (r2 modify = 0.189; P < 0.001) and monthly total atmospheric precipitation lagged by 1 calendar month (r2 modify = 0.156; P < 0.001) together explained 81% of the monthly variability in malaria incidence. At the midland dam, village altitude to reservoir shoreline lagged past 1 calendar month (r2 = 0.398; P < 0.001), monthly reservoir h2o level lagged by ii months (rtwo change = 0.266; P < 0.001) and monthly total atmospheric precipitation lagged past two months (rii = 0.221; P < 0.001) explained 71.1% of variation in monthly malaria incidence. At the highland dam, hamlet altitude to reservoir shoreline lagged by 1 month (r2 = 0.324; P < 0.001), monthly change in reservoir h2o level lagged by two months (r2 change = 0.374; P < 0.001) and monthly mean minimum temperature lagged by ii months (rii change = 0.068; P < 0.001) explained 76.5% of variation in monthly malaria incidence. Overall, dam-associated factors, such every bit altitude to shoreline or the magnitude of h2o level changes, were establish to exist the most important variables contributing to malaria incidence in nearby villages.

Discussion

This study revealed that dam-associated ecology factors and local meteorological drivers influence malaria transmission effectually large dams in Ethiopia. The importance of these factors, however, varied across lowland, midland and highland dam sites. Interestingly, a village'south altitude from the nearest reservoir shoreline was the virtually important variable at all three dams, explaining 47, twoscore and 32% of the monthly variation in malaria incidence at the lowland, midland and highland dams, respectively. This indicates the function that dams play in malaria transmission by providing favourable breeding habitats for malaria mosquitoes. Previous studies indicated that An. arabiensis, the primary malaria vector mosquito in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, breeds forth reservoir shorelines [12, 14].

Monthly reservoir water level (lagged by 2 months) was also positively correlated with monthly malaria incidence at the lowland and midland dams. This suggests that during periods of high water level, reservoir shorelines get closer to villages (as shown past distance) and contribute to increased musquito abundance as the outcome of mosquito breeding in reservoir shoreline habitats. The present results also signal that the shorter the distance between villages and reservoir shoreline the higher the malaria incidence. This is in agreement with the findings of a recent study that documented enhanced larval abundance of An. arabiensis and An. pharoensis, the major malaria vectors in Ethiopia, in lowland and midland dam areas [14]. Similar observations were also made around Lake Victoria in Kenya where the abundance of An. gambiae complex (of which An. arabiensis is a member) substantially increased during high water levels [28]. In southwest Ethiopia, Sena et al. [29] institute that elevation and distance from reservoir were important factors determining malaria transmission effectually Gilgel-Gibe. Generally, the meaning association betwixt hamlet distance from reservoir shoreline and malaria incidence confirms the function of dams in malaria transmission at all 3 dam settings.

Whilst precipitation was the about important meteorological factors associated with malaria incidence at the lowland and midland dams, minimum temperature appeared to be a pregnant driver of malaria incidence around the highland dam. In fact, precipitation is strongly correlated with reservoir water level as periods of loftier water level follow heavy rains betwixt June and August. Teklehaimanot et al. [30] indicated that precipitation is the well-nigh of import factor for malaria transmission in the lowlands of Ethiopia as mosquito convenance is largely limited past h2o availability. Summit malaria transmission often follows the primary rainy flavour in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia [31]. Precipitation has a direct and indirect effect on malaria transmission around dams: information technology increases reservoir water level which creates potential mosquito breeding habitats along the shorelines closer to reservoir villages, and forms rain pools that mosquitoes use for breeding.

The issue of minimum temperature on malaria transmission in the highlands has long been recognized [32,33,34,35]. Temperature is a cardinal determinant of the length of mosquito and malaria parasite life bicycle [34, 36]. For instance, at 16 °C, larval development may take more than 45 days (reducing the number of mosquito generations and putting the larvae at increased take chances of predators), compared to simply 10 days at 30 °C [30]. All the same, temperature increases above 30 °C have been regarded as detrimental to parasite and mosquito development [36]. By affecting the elapsing of the aquatic stage of the mosquito life bike, temperature determines the timing and affluence of mosquitoes following adequate rainfall. The feeding frequency of mosquitoes is also affected past temperature—an increase in temperature leads to increased proportions of infective mosquitoes [37]. However, the effect of temperature largely depends on elevation: as summit increases, temperature decreases, which affects both mosquito and malaria parasite evolution [38]. The minimum temperature required for the development of P. falciparum and P. vivax is approximately 18 °C and xv °C, respectively, limiting the spread of malaria at higher altitudes [39]. There is also a relationship between increasing distance and decreasing mosquito abundance in African highlands [38]. In lite of future climatic change, higher temperatures could also facilitate faster desiccation of convenance habitats, compromising larval development. These effects of minimum temperature might explain the significance of this gene in determining malaria manual rates around the highland dam in the nowadays study.

Monthly NDVI (lagged by ane and two months) was significantly correlated with malaria incidence, particularly around the lowland dam. Several studies accept shown a positive significant correlation between NDVI in the preceding month and malaria in West, Central and East Africa [40,41,42]. Notwithstanding, it should be noted that temporal variation in NDVI is often highly correlated with rainfall specially in semi-barren lowlands, as shown in the present report and others [43, 44]. In the Sudanese Savannah region of Mali, Gaudart et al. [42] reported NDVI to be an of import predictor of the total surface surface area of breeding sites, as NDVI values increase with soil wet. In Eritrea, Graves et al. [45] found that NDVI is a meliorate predictor of malaria incidence than rainfall. In the absence of rainfall data, NDVI can thus be used to predict malaria risk in lowland areas.

Monthly change in reservoir h2o level (lagged by 2 months) was one of the most important determinants of monthly malaria incidence effectually the lowland and midland dams. The charge per unit of water level change has previously been shown to determine availability of shoreline habitats for mosquito breeding effectually [12]. Faster water level drawdown rates, adamant by the magnitude in water level change between consecutive months, were associated with depression larval musquito affluence and fewer shoreline puddles [46]. Similarly, the present study showed that a chop-chop receding reservoir shoreline was associated with lower malaria incidence rates (Fig. 6). Increasing water levels, which likewise shorten the distance from villages to shorelines, were positively correlated with increasing malaria incidence. This likewise explains the seasonality of malaria effectually dam villages which peaks immediately later the rainy season when reservoirs fill up. Reservoir water level is thus an important factor underpinning the production of shoreline mosquito breeding habitats.

Understanding the various factors that contribute to malaria transmission is crucial in order to forecast malaria risk and devise affliction command tools. Although evidence for the full general impact of dams on malaria is well documented in sub-Saharan Africa [5, half-dozen, 15], specific factors responsible for increased malaria effectually dams take been less clear. The present study has for the first time identified environmental and meteorological factors associated with increased malaria manual around dams at different ecological settings. Its findings underscore the function of reservoir h2o levels in malaria transmission nearby, and besides allow the potential of using reservoir water level management for malaria vector control to be assessed. Reservoir h2o level direction was effectively implemented to disrupt malaria vector breeding in habitats in the Tennessee Valley, U.s.a. [47]. A recent study in Ethiopia assessed the efficacy of this approach under field experiments and found that faster drawdown rates suppress larval development [46]. Even so, this arroyo has never been applied to African dams. Future research should investigate the potential of using water level management for malaria control in existing African dams.

This written report has three main limitations. First, the malaria information used were retrospective data with a 75–82% level of completeness. Agile case detection would have improved confidence in the present findings relative to retrospective datasets. 2nd, the difference in malaria control use (e.g., bed nets) among the report dams was not considered in the modelling. Third, entomological information were not included in the modelling, although these would have contributed to the biological explanation for the lag times observed in the response of malaria infection cases to some ecology variables.

Decision

Dams intensify malaria transmission in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. The rate of reservoir water level alter and hamlet distance from reservoir shorelines were both constitute to exist key malaria determinants around dams. As many dams are currently planned in sub-Saharan Africa, understanding the factors underlying increased malaria transmission is crucial to inform where to locate dams and communities at higher risk of the disease. Health authorities and dam operators should explore mechanisms to optimize dam operation to suppress nearby malaria transmission. Effective water level management, augmented with the existing vector control approaches, could assist adjourn the malaria run a risk around big dams in Africa.

References

-

WHO. World Malaria Report 2018. Geneva: World Wellness Organization; 2018.

-

Patz JA, Olson SH. Malaria risk and temperature: influences from global climate modify and local land apply practices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5635–6.

-

Stern DI, Gething Pw, Kabaria CW, Temperley WH, Noor AM, Okiro EA, et al. Temperature and malaria trends in highland Eastward Africa. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24524.

-

Jobin W. Dams and disease: Ecological design and health impacts of large dams, canals and irrigation systems. London: Due east&FN Spon; 1999.

-

Keiser J, de Castro MC, Maltese MF, Bos R, Tanner M, Vocaliser BH, et al. Effect of irrigation and large dams on the burden of malaria on a global and regional scale. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:392–406.

-

Kibret S, Wilson GG, Ryder D, Tekie H, Petros B. The influence of dams on malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. EcoHealth. 2015;14:408–19.

-

Atangana South, Foumbi J, Charlois One thousand, Ambroise-Thomas P, Ripert C. Epidemiological report of onchocerciasis and malaria in Bamendjin dam area (Republic of cameroon). Med Trop (Mars). 1979;39:537–43 (in French).

-

Freeman T. Investigation into the 1994 malaria outbreak of the Manyuchi Dam area of Mbberengwa and Mwenezi Districts, Zimbabwe. 1994.

-

Ghebreyesus TA, Haile M, Witten KH, Getachew A, Ambachew M, Yohannes AM, et al. Incidence of malaria among children living well-nigh dams in northern Ethiopia: community based incidence survey. BMJ. 1999;319:663–vi.

-

Lautze J, McCartney M, Kirshen P, Olana D, Jayasinghe G, Spielman A. Result of a big dam on malaria risk: the Koka Reservoir in Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:982–9.

-

Mba CJ, Aboh IK. Prevalence and direction of malaria in Ghana: a case written report of Volta region. Afr Pop Studies. 2007;22:137–71.

-

Kibret South, Lautze J, Boelee Due east, McCartney M. How does an Ethiopian dam increment malaria? Entomological determinants around the Koka reservoir. Trop Med Int Wellness. 2012;17:1320–8.

-

Yewhalaw D, Getachew Y, Tushune K, Kassahun W, Duchateau Fifty, Speybroeck N. The issue of dams and seasons on malaria incidence and Anopheles abundance in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:161.

-

Kibret South, Wilson GG, Ryder D, Tekie H, Petros B. Malaria bear on of big dams at dissimilar eco-epidemiological settings in Ethiopia. Trop Med Wellness. 2017;45:iv.

-

Kibret S, Lautze J, McCartney K, Wilson GG, Nhamo 50. Malaria affect of large dams in sub-Saharan Africa: maps, estimates and predictions. Malar J. 2015;fourteen:339.

-

Lindblade KA, Walker ED, Wilson ML. Early warning of malaria epidemics in African highlands using Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae) indoor resting density. J Med Ent. 2000;37:664–74.

-

Coetzee M, Craig Thousand, le Sueur D. Distribution of African malaria mosquitoes belonging to the Anopheles gambiae complex. Parasitol Today. 2000;sixteen:74–7.

-

Sinka ME, Bangs MJ, Manguin S, Coetzee Thou, Mbogo CM, Hemingway J. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle E: occurrence information, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:117.

-

National Planning Commission. Growth and transformation program 2 (GTP Two) (2015/16-2019/20). Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Commonwealth of Ethiopia; 2016.

-

Central Statistical Bureau. National population census results. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Fundamental Statistics Bureau; 2007.

-

Birhanu Yard, Alamirew T, Dinka MO, Ayalew Due south, Aklog D. Optimizing reservoir operation policy using adventure constraint nonlinear programming for Koga irrigation Dam, Ethiopia. H2o Resour Manag. 2014;28:4957–70.

-

Kibret South, McCartney Yard, Lautze J, Jayasinghe Yard. Malaria transmission in the vicinity of impounded water: evidence from the Koka reservoir, Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. IWMI Inquiry Written report 132. Colombo, 2009.

-

Sori Thousand, Zewdie O, Tadele M, Samuel A. External quality assessment of malaria microscopy diagnosis in selected health facilities in Western Oromia, Ethiopia. Malar J. 2018;17:233.

-

European Space Agency. European Space Agency image repository. https://www.esa.int/spaceinimages/Images. Accessed 12 May 2016.

-

United States Geological Survey. 2015. Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) dataset. https://world wide web.usgs.gov/products/information-and-tools/existent-time-data/remote-land-sensing-and-landsat. Accessed 12 May 2016.

-

Hay SI, Snowfall RW, Rogers DJ. Predicting malaria seasons in Republic of kenya using multitemporal meteorological satellite sensor data. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:12–20.

-

Simonoff JS, Chatterjee S. Handbook of regression analysis. New Jersey: Wiley; 2012.

-

Minakawa N, Sonye Thousand, Dida GO, Futami 1000, Kaneko Due south. Contempo reduction in the h2o level of Lake Victoria has created more than habitats for Anopheles funestus. Malar J. 2008;seven:119.

-

Sena L, Deressa W, Ali A. Dynamics of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in a micro-ecological setting, Southwest Ethiopia: effects of distance and proximity to a dam. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:625.

-

Teklehaimanot Hd, Lipsitch M, Teklehaimanot A, Schwartz J. Weather-based prediction of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in epidemic-prone regions of Ethiopia. I. Patterns of lagged weather effects reflect biological mechanisms. Malar J. 2004;3:41.

-

Ministry building of Health. National Malaria Control Guidelines. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Ministry of Health; 2012.

-

Lindsay SW, Martens WJ. Malaria in the African highlands: past, nowadays and futurity. Bull Earth Wellness Organ. 1998;76:33–45.

-

Craig MH, Snowfall RW, le Sueur D. A climate-based distribution model of malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:105–11.

-

Blanford JI, Blanford S, Crane RG, Mann ME, Paaijmans KP, Schreiber KV, et al. Implications of temperature variation for malaria parasite development beyond Africa. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1300.

-

Mordecai EA, Paaijmans KP, Johnson LR, Balzer C, Ben-Horin T, Moor E, et al. Optimal temperature for malaria manual is dramatically lower than previously predicted. Ecol Lett. 2013;sixteen:22–30.

-

Lyons CL, Coetzee M, Chown SL. Stable and fluctuating temperature effects on the development rate and survival of 2 malaria vectors, Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus. ParasitVectors. 2013;6:104.

-

Paaijmans KP, Blanford S, Bong AS, Blanford JI, Read AF, Thomas MB. Influence of climate on malaria transmission depends on daily temperature variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.s.. 2010;107:15135–9.

-

Bødker R, Akida J, Shayo D, Kisinza W, Msangeni HA, Pedersen EM, et al. Relationship between altitude and intensity of malaria transmission in the Usambara Mountains, Tanzania. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:706–17.

-

Gosoniu L, Vounatsou P, Sogoba N, Smith T. Bayesian modeling of geostatistical malaria gamble data. Geospatial Health. 2006;1:127–39.

-

Gemperli A, Sogoba N, Fondjo Due east, Mabaso M, Bagayoko M, Briët OJ, et al. Mapping malaria transmission in W and Central Africa. Trop Med Int Wellness. 2006;11:1032–46.

-

Gomez-Elipe A, Otero A, Van Herp Thousand, Aguirre-Jaime A. Forecasting malaria incidence based on monthly case reports and environmental factors in Karuzi, Burundi, 1997–2003. Malar J. 2007;half dozen:129.

-

Gaudart J, Touré O, Dessay Northward, Dicko A, Ranque South, Wood 50, et al. Modelling malaria incidence with ecology dependency in a locality of Sudanese savannah surface area, Republic of mali. Malar J. 2009;8:61.

-

Wayant NM, Maldonado D, de Arias AR, Cousiño B, Goodin DG. Correlation between Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and malaria in a subtropical rain woods undergoing rapid anthropogenic alteration. Geospatial Health. 2010;4:179–90.

-

Baeza A, Bouma MJ, Dobson AP, Dhiman R, Srivastava HC, Pascual M. Climate forcing and desert malaria: the effect of irrigation. Malar J. 2011;ten:190.

-

Graves PM, Osgood DE, Thomson MC, Sereke K, Araia A, Zerom M, et al. Effectiveness of malaria command during changing climate atmospheric condition in Eritrea, 1998–2003. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;xiii:218–28.

-

Kibret S, Wilson GG, Ryder D, Tekie H, Petros B. Can water-level management reduce malaria mosquito abundance around big dams in sub-Saharan Africa? PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196064.

-

Hess AD, Kiker CC. Water level management for malaria command on impounded waters. J Natl Malar Soc. 1944;3:181–96.

Authors' contributions

SK, GGW and DR conceived the study; SK nerveless and analyzed the information and drafted the manuscript. GGW and DR involved in data interpretation and manuscript preparation. GGW, DR, HT, BP revised the typhoon for intellectual inputs. All authors read and canonical the concluding manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Kefyalew Girma for his support with satellite data analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data used for this written report are presented here. Raw data tin be obtained past contacting the corresponding writer.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was funded by the University of New England, Commonwealth of australia, and the International Foundation for Science (IFS, Grant #Due west/4752-2).

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in whatever medium, provided you lot give advisable credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and signal if changes were fabricated. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/ane.0/) applies to the information made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Kibret, S., Glenn Wilson, Thousand., Ryder, D. et al. Environmental and meteorological factors linked to malaria transmission effectually big dams at three ecological settings in Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. Malar J 18, 54 (2019). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12936-019-2689-y

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-2689-y

Keywords

- Malaria

- Climate

- Environment

- Reservoir shoreline

- Water level

- Dam

- Ethiopia

Source: https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-019-2689-y

Publicar un comentario for "what are environmental factors that contribute to malaria"